Research

A Brief Summary of the Research Inga Alley Cropping

Inga edulis trees in flower, Cameroon. Photo by Gaston Bityo.

The Inga alley cropping system is based on about two decades of research and field trials (1). Rainforest Saver came into being after this research was done and the effectiveness of Inga alley cropping had been established. We are promoting it as a practical alternative to the destructive practice of slash and burn agriculture.

The aim of this section is to give only a brief summary demonstrating the validity of the system. The references at the end may serve as a starting point for those who wish to delve more deeply.

This is not the place to repeat definitions, explanations, evaluations and descriptions of alley cropping in general. We refer the reader to E.C.M. Fernandes’s excellent and very readable account for this (2). Yet this research alone wasn’t enough for a full realisation of the potential of the Inga tree for alley cropping. Indeed Fernandes’s original conclusions cast some doubt on the value of alley cropping in general, except where the tree hedgerows reduce erosion on sloping sites. This last point has been well demonstrated in the Inga system, for example where hedges of Inga planted on slopes survived hurricane Mitch.

The full discovery of how well Inga alley cropping works was due to the meticulous research of M. R. Hands and his co-workers. This consisted not only of extensive laboratory studies, for example of soil samples, but also field studies and finally acceptance trials with farmers, with very positive results. Much of this research is reported in more detail in the references at the end of the section, particularly his account of the research to the EU funders (1).

Valuable features of the Inga tree, and how these are made use of for alley cropping

-

The Inga tree is widespread and native to many parts of South and Central America. Some Inga species are much more suitable than others. The most frequently used species, Inga edulis, is native to Amazonian Brazil, Bolivia, Peru, Ecuador and Colombia, but has been introduced widely to many other places (1). This means it is available and likely to grow successfully over a large area, without the potential problems of introduced non native species.

-

It grows in hot, humid climates between 26°S and 10°N, and up to 1600 m elevation. It is most widespread in areas without a dry season (Andean South America, western Brazil) or with a dry season of three to four months and minimum annual rainfall of around 1200 mm. It can tolerate short droughts, although in its natural range some rain falls every month (1).

-

It grows well on the acid soils of the tropical rainforest and former rainforest soils. Much of the land available to poor subsistence or slash and burn farmers is of this type.

-

Inga is a leguminous tree that fixes nitrogen (converts nitrogen from the air into a form usable by plants). It can do this because nitrogen-fixing bacteria grow symbiotically with it forming nodules on its roots.

Root nodules in an Inga seedling. Photo by Gaston Bityo

Prunings of thick leaves in an Inga alley, Ecuador

-

It grows fast.

-

It has thick leaves that when left on the ground after pruning form a thick mulch cover that protects the soil and the roots of both the trees themselves and the crops from the sun and heavy rain. This create a permanent cover, so the soil is never exposed.

-

This mulch/green manure builds up after subsequent prunings and the crops feed mostly on the decomposing matter from earlier, not the most recent, prunings (1). The latter are important as they form a protective layer that keeps moisture and an even temperature in the lower layers (3).

-

The branches spread out to form a thick canopy, which cuts off light from the weeds below so that the weeds die.

-

Any weeds that are left are smothered by the mulch from the prunings of the thick leaves. This also prevents the subsequent regrowth of weeds in the alley. Light is then let into the alley for the crops. Weed suppression is a very important component of the alley cropping system. “Weeds are estimated to account for up to 50% of the loss in field production in the tropics. Worldwide, a 10% loss of agricultural crop production can be attributed to the competitive effect of weeds, with over 50% of total farm labor and 40% of production costs spent on combating them, equivalent to an estimated 10-15% of the total value of agricultural production” (3).

-

Once the Inga system has been established the farmer’s workload is substantially reduced. The farmer plants the crops into the top layer of the soil under the mulch by using a planting stick to make a hole. Crops like maize and beans have bigger, stronger seeds than the weeds and can push their way up through the mulch. The weeds, which have smaller seeds, cannot do so (5).

-

The Inga withstands careful pruning year after year. It is however important not to cut it too far down. A little bit of green leaf should be left. Some alley cropping systems cut the trees very low, for example one account says: “Once the trees reach shoulder height (1-2 metres high) they are cut right back to just 20-30 cm in height”(6). This may work for some trees, but not for the Inga.

-

There are little nectaries at the base of the Inga leaf clusters, which secrete a sweet liquid that forms a food for ants. The resident ants that live on the Inga tree may protect it from other damaging pests (8).

Ants on Inga leaf nectaries. Photo by T.D. Pennington.

Fernando with a load of Inga pods. Photo by T.D. Pennington.

-

Rows of trees take up valuable farmland, so farmers like trees whose prunings are also useful. Inga is valued as a clean burning fuel that provides a good amount of heat for cooking. When the Inga is pruned a lot of firewood is produced, which farmers value highly. A one tenth hectare plot produced enough firewood to last three months in the kitchen stove (1). The fruits can also be eaten, but in alley cropping the trees have to be pruned before they flower or set fruit.

Inga alley cropping differs from many other types of alley cropping in that it aims to imitate the conditions on the floor of the rainforest. Repeated layers pruning slowly decompose forming a permanent protective layer of mulch over the soil. The soil never dries out and is always protected from the impact of heavy rain. This encourages the formation of a shallow rooting mat within the mulch and the top layers of the soil, similar to the conditions in an actual rainforest floor. There is also a tap root which holds the tree securely in place. Many other alley cropping systems have done the opposite and used trees with a long taproot and fewer side roots to both lessen competition between tree and crop roots growing in the ally and hopefully bring nutrients up from deeper soil layers (3,6,7). In the Inga system the shallower rooting system avoids most of the deeper pests in the soil, leading to increased crop yields. Trials have compared three conditions, Inga alley cropping, alley cropping using Erythrina fusca and Gliricidia sepium (E/G plots) as the hedge trees with clear control plots. Beans grown in the control plots and E/G plots were found to be widely infected with root-knot nematode cysts, which were presumably present in the entire site. The roots of the E. fusca were also infected. But beans grown in the Inga alleys had formed a shallower root-mat into the mulch and both they and the Inga were free of the infestation. The clear plots on the other hand showed typical vertical taproots which reached deeper down and were infected (5). When there is no permanent protective mulch cover a root mat cannot form because it would be exposed too much to scorching sun and heavy rain, so the roots have to seek protection deeper down.

Hands tried many different trees and species of Inga and found Inga edulis and Inga oerstediana to work best (1,5). Comparing Inga alleys with alleys using a mixture of Gliricidia sepium and Erythrina fusca whereas initial crop production in the E/G plots was acceptable, crop yields fell after two or three years while the weeds increased. Only the Inga plots, with Inga edulis and Inga oerstediana being the best, maintained their level of production.

The shallower rooting system also avoids toxic elements like excessive aluminium, which are deeper down in the soil. The roots can absorb nutrients from the decomposing prunings when the soil itself may be very poor. As in the rainforest, the trees recycle the nutrients not used by the crops and removed by harvesting (5).

Phosphorus is mentioned in the literature as being a very relevant nutrient that may be in short supply in the sort of leached, acid soils that slash and burn farmers often have to use (3). Hands tried different nutrients (fertilizers) on a number of plots and found that the only one that made a difference was phosphorus (5). It improved all growth including weeds (if there were any, Inga plots were generally free of them), crops and the Inga trees themselves. Hands commends ground rock phosphate applied to the mulch. It is cheap and less likely to be washed away than more expensive fertilizers. This is the only chemical input that he used. One initial application was found to improve the crops for at least six subsequent years, indicating that when the mycorrhizae take up the phosphorus it is taken up by the trees and later made available for the crops when the trees are pruned. The effects of the initial application of phosphorus may indeed last longer, but the study ended after six years (1). Hands thought that this amount of rock phosphate would be easily affordable to the farmer. Other inputs may well be needed later, but it is likely that the Inga will also efficiently recycle them. However in all our work to date in Ecuador and Cameroon we have not needed to add any rock phosphate. It may be that the soils that Hands was experimenting on in Honduras were much more degraded, though some of the soils we have worked with in Cameroon were also so degraded that they produced no crops to speak of without the Inga. For an up to date discussion of the role of phosphorus see (11).

Hands analysed hundreds of soil samples taken at every stage in the slash-and-burn simulation to discover the role of phosphorus. It had been thought that the ash from burning the forest provided the crops with the phosphorus they needed. But Hands found it was being washed out before the crops could absorb it. He realised that the ash on the soil has the same effect as liming a compost heap: it speeds up the process by which soil microbes decompose organic matter, such as dead leaves. This was releasing the phosphorus for the crops. But the microbes needed organic matter to live on. Initially this came from the organic matter from the felled forest. After two years this was used up and the microbes died and no more phosphorus was released. With no phosphorus-retrieving trees there to take it up, any remaining phosphorus was washed out of the soil by rainfall and the crops failed (1).

One small scale comparison reported a fourfold increase of maize yield when the farmer took up Inga alley cropping (9).

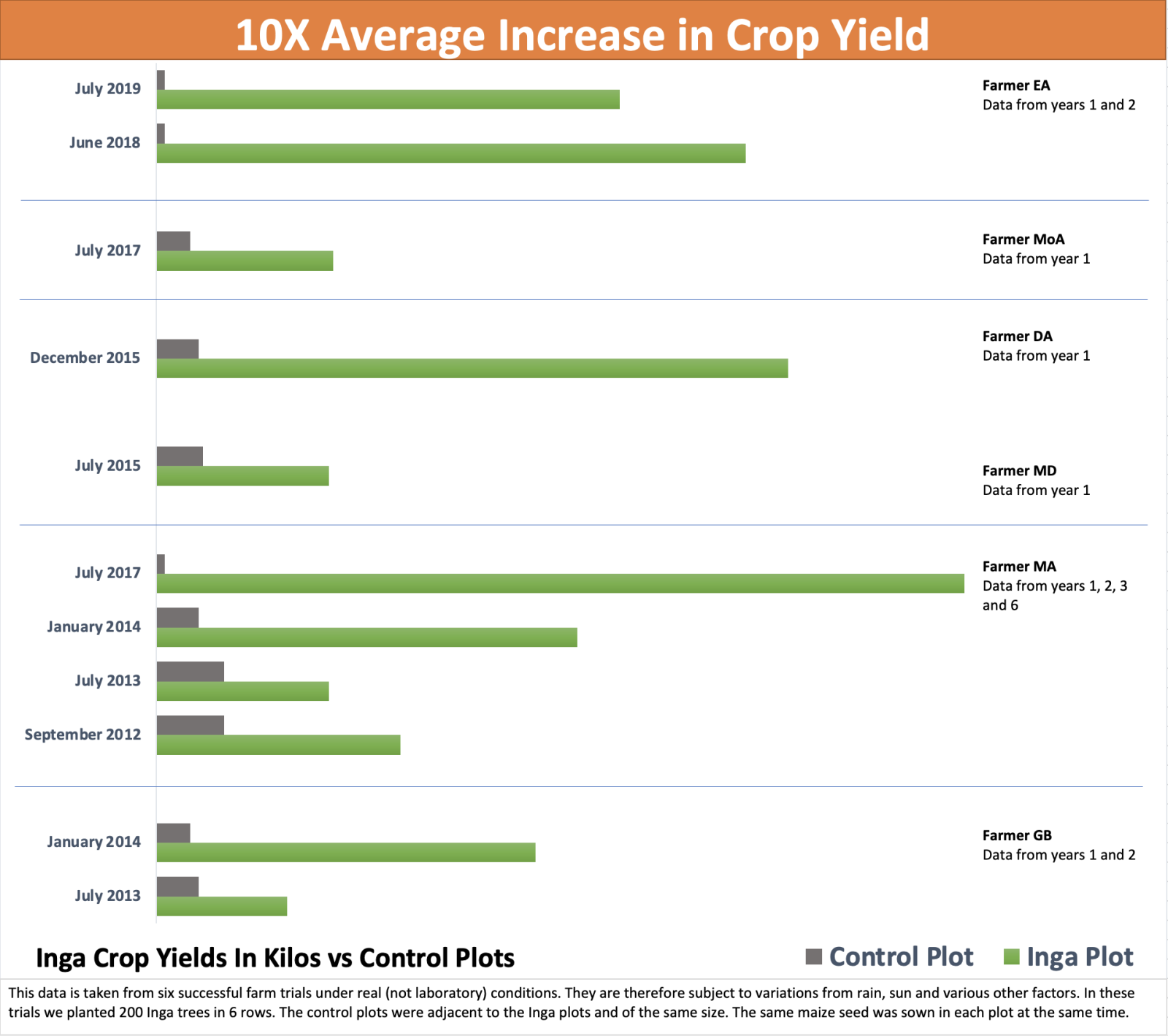

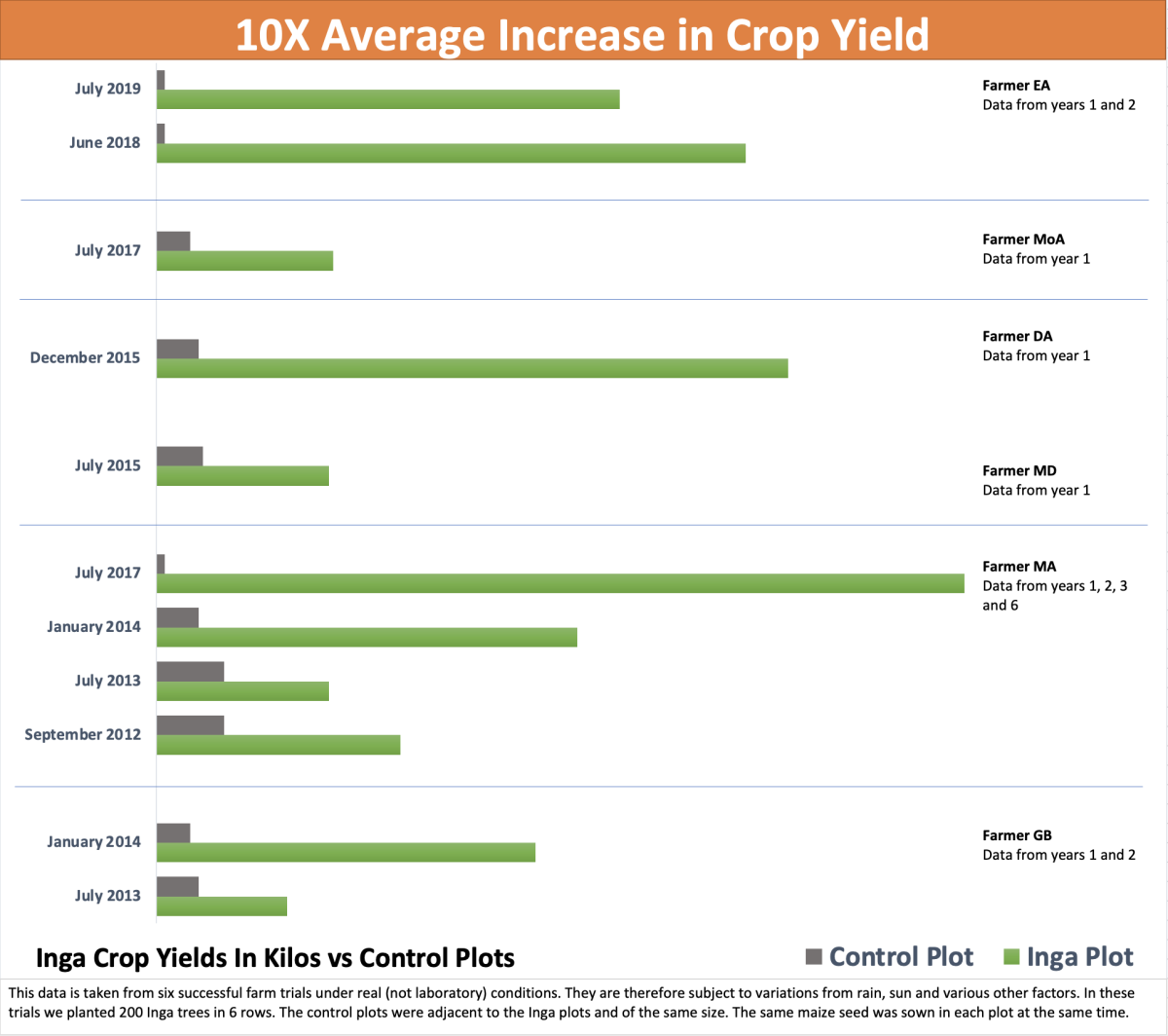

More recently we have done some some rough experiments in Cameroon in farmers’ plots, supervised by our local Cameroon partner, Gaston Bityo. Maize was planted in Inga plots and adjacent plots of the same size without Inga, at the same time and using the same seed. The harvests were weighed. On several farms it was possible to repeat this over two to six years. The plots were 300 m2 using 200 Inga trees each for the Inga plots. In all the plots the yields on these degraded soils from the comparison plots were tiny, rarely more than 5 kg. There was great variability in the Inga plot yields, and working in the farmers’ fields, in different places made close supervision impossible. Mr. Gaston was there for the sowing and the harvest, but not often in between, so that it did happen that hungry farmers ate some of the crop before it was weighed. So some yields were estimated. But in spite of these difficulties there was no doubt that the Inga re-fertilized the soil and gave good yields. These varied greatly, and we are currently (2022) trying to look into the reasons for this variation. The results are shown in the diagram above.

No system, however perfect, is of practical use if the farmers do not want to take it up. Early trials of the Inga system with farmers proved very positive. Those who tried it were very impressed with the results and generally wanted to increase the amount of land they have under Inga alley cropping (1). Several thousand farmers were taken through the demonstration facilities and they showed great enthusiasm for adopting the system.

Our later experience has also been that many farmers are keen to try it, but do need to see the results for themselves before they are convinced. So we often start off with very small plots that are increased later. This also allows us supply more farmers with the limited amount of seed or seedlings that we can supply at any one time.

Many different crops have been grown in the Inga plots, such as maize, beans, cocoyams, cassava, pineapples, vanilla, passionfruit.

Farmers showing their vanilla crop. Photo by FUPNAPIB

Biological corridors and afforestation and reforestation.

The Inga can also be used as a nurse tree to reclaim degraded land for forestry. This has been successfully done to establish a biological corridor in Honduras (1).

To do this the Inga are planted less densely and not pruned as in alley cropping. They are planted in a 4-metre diagonal pattern, with one tree in four omitted. When planted into a degraded site covered by pervasive grasses initial slashing of these weeds may be needed repeatedly at the start to allow the Inga to become established. The Inga are able to take over in time. Once the Inga branches have begun to form a tree cover over the site, the gaps are planted with whatever tree species is required. It can be very difficult to establish such trees directly into invasive grasses. Some pruning of the Inga may be required to enable the desired trees to get more light. At CURLA (part of the Autonomous University of Honduras) two of the Inga species achieved site-capture within 2 years; and the corridor now functions as shelter and habitat to many species of animals, insects and birds (10).

References

- Hands, M.R. Alley cropping as a sustainable alternative to shifting cultivation: Phase III Final Report. Commission of the European Communities directorate general 1. North-South relations. Tropical forests budgetary line project HND// B7‑6201 / IB / 97 / 0533(08) June 2002.

- Fernandez E.C.M. In Pennington, T.D. and Fernandes E.C.M. The Genus Inga: Utilization The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 1998

- Rippin et al.1994.

- Hands, M.R. The uses of Inga in the acid soils of the rainforest zone: Alley-cropping sustainability and soil-regeneration. In: Pennington, T.D. and Fernandes E.C.M. (Eds.) The Genus Inga: Utilization The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 1998

- Hands, M.R. The uses of Inga species in alley-cropping; a proven and sustainable alternative to slash-and-burn agriculture in the rain-forest. Unpublished manuscript July 2003

- Sustainable Harvest International http://www.sustainableharvest.org/techniques/alley-cropping

- Pennington, T.D. and Fernandes E.C.M. The Genus Inga: Utilization The Royal Botanic Gardens, Kew 1998

- Pennington, T.D. Presentation given to the Inaugural Meeting of the Rainforest Saver Foundation. 17thSeptember, 2005

- Melville, A. Trip to Honduras, Part 2. http://rainforestsaver.org/html/antonys_trip_part_2.html. 2008.

- Hands, M.R. The Inga Project: 2005 and onwards. Unpublished manuscript 2005

- The search for a sustainable alternative to slash-and-burn agriculture in the World’s rain forests: the Guama Model and its implementation. Michael Hands. https://royalsocietypublishing.org/doi/10.1098/rsos.201204